New Pain During Exercise

Experiencing a sudden increase in pain during exercise is incredibly frustrating, especially when there’s no obvious explanation, and even more so when things have seemingly been going really well!

Over a long enough time frame, we will all likely experience an episode of unfamiliar pain. In fact, pain is a normal part of life that protects us from real or potential danger. Whilst it’s common to have pain as a result of an injury, it’s vital to recognise that pain does not always mean damage. Take for example amputees that experience phantom limb pain, a phenomenon where they feel pain in their missing limb. Pain occurs in the absence of tissues! So it appears pain is much more complex than once thought.

Let’s take another example. We’ve all had an experience where you touch something hot and instinctively pull your hand away. The pain might be severe, but there is no damage to your skin. These are just a couple of examples showing that hurt does not equal harm. If you are unfamiliar with this concept, we highly recommend reading this article for a more in depth discussion of pain, before you go any further.

If you’re still not convinced, that’s fine. The idea that pain always means injury seems to make logical sense and is very well ingrained into society. But let’s move on…

You’re doing an exercise, let’s say a squat, and all of a sudden you have excruciating knee pain. You stop, clutch your leg and sit down. After a moment the pain subsides so that you’re no longer gasping for air.

It’s at this point you probably ask the question: What do I do now?

This is one of the most common questions we are asked, because it happens to people of all ages, all over the body, whether they’re a long term exerciser, or just starting out. So whether you have a sore back, knee, hip, shoulder or something else, the following steps will help you on your way to getting moving again.

Before we get started, through every stage of this process it’s important to remember this. Tolerable pain during exercise is okay. If the symptoms don’t leave you feeling debilitated at the time, or after the exercise, it’s usually safe for you to continue. If however, the pain is beyond what you can handle, makes exercise completely distressing or stops you from doing your daily tasks afterwards, you should back off your exercise.

The Process

- Double Check

So you’ve ceased exercising, and the pain has settled, and you’re feeling a little better. You might still have some mild symptoms but it’s not excruciating to keep still or perhaps walk or move the body part around a little. Pain can happen for all sorts of reasons and is influenced by lots of different factors. Have you ever had a weird unexplained pain that comes out of the blue, is there for a few seconds, and then disappears, never to be felt again? A similar experience can happen during exercise, so it’s a good idea to retry the culprit movement to see if the pain occurs again. Let’s go back to the squat example. You try one or two more gentle squats, and you notice the pain is far less threatening or nearly completely gone. Hooray! OR… you find the pain is there again and is just as bad as it was initially, or even worse… Try to stay calm. In the next few steps we will go through what to do next.

- The current session

If the pain is intolerable for the movement that initially provoked the symptoms, you may still be able to complete some of the other exercises. For example a sore knee usually won’t stop you from doing upper body movements, and a sore shoulder often won’t stop you from exercising your legs. There are obvious exceptions to this of course, anyone who has experienced an acute episode of back pain will understand how nearly any movement can bring on pain.

If you can, completing some form of workout will hopefully leave you feeling a little more positive, and is of course very beneficial for your health and fitness - something you will want to maintain throughout your recovery.

Once you’ve finished your workout, hopefully you are able to manage most of the rest of your tasks for the rest of the day. If you need to take it easy for 48h while the area is still very sensitive, that is to be encouraged as the symptoms settle down. However, looking forward, we must draw our attention to getting moving normally again.

- The next session

So 2-3 days have passed, you’ve kept doing most tasks, but have taken it a bit easier on the painful region. You might wonder: rest has made it feel better… shouldn’t I continue to rest until the pain completely resolves?

It’s a fair question, but the answer is almost always ‘no’.

Rest usually makes things feel better at the time, but in the longer term it can make us more sensitive. To understand why this is the case, we need to understand the principle of physiological adaptation. Whenever the body undergoes a stress (like exercise), it throws the body out of it’s comfort zone. The body doesn’t like this one bit! It anticipates that it will undergo that stress sometime again in the future, and to make sure it can stay within it’s comfort zone, it recovers to a level beyond its original baseline. This happens in the muscles, joints, bones and many other tissues, but it also causes the nervous system and brain to be more resilient to that stress. The opposite is also true. If we take away the stress (exercise) altogether, the body decides to put the resources that would otherwise be used to adapt to the stress, towards something else. This is why people who are sedentary have very low levels of strength and muscle mass - because they aren't conditioned to exercise. This process of deconditioning makes our bodies more sensitive to stress and this in turn increases the likelihood of pain.

So, it is paramount that we find some level of exercise that is manageable, not only to maintain good health, but to prevent the body and brain from becoming overly sensitive. Ideally, this involves exercises that are specific to the activity that caused the pain initially.

NOTE: This is just one factor in why exercise can help with pain, with a very simple explanation. For more information, we highly recommend the book Explain Pain by Butler and Moseley.

So, let’s workout what you can do in your next session using knee pain as an example. Hopefully you’re able to manage the upper body movements, and you might even manage movements like deadlifts without too much trouble. But doing the squat is intolerable. Here are the steps to take to allow you to continue any exercise that is causing an intolerable level of pain:

- Weight - the first step is to try reducing the weight for that exercise. So if you’re holding a 10kg weight for the squat, try 5kg. If that’s too much, try a bodyweight squat. If you can find a weight where you can tolerate the symptoms, that’s the starting point.

- Range of motion - if going to the minimum weight doesn’t help, the next step is to try reducing the range of motion. So for a squat, you can try a shallower squat. Even if the movement is still small and you feel like you’re not achieving anything, it’s still a starting point that will help maintain condition and reduce sensitivity.

- Substituting a similar exercise - if you’ve tried reducing the weight and range of motion with no success, it’s time to try something different. The exercise to sub in is ideally as similar as possible whilst allowing you to perform it without unmanageable pain. An example is performing a sit to stand from a chair instead of a squat. If anything that resembles the squat is too painful, performing a deadlift where you don’t bend your knees might be suitable. The important thing is finding SOMETHING to do instead.

- The following sessions

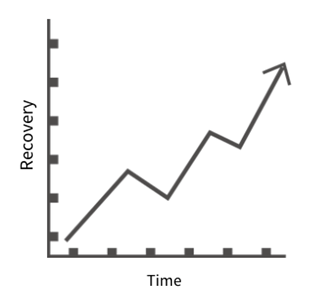

For some pain experiences, it will only last a few days, whilst others can remain sensitive for a much longer time. Of course, if you are concerned about something, it’s best to check with a healthcare professional. Regardless of the time course, once you have found your tolerable re-entry point, all that remains is to gradually build up, just as you would have been doing pre-pain. This can be done by increasing weight, or range of motion as you feel comfortable to do so. It’s important to remember that the rehabilitation process is rarely linear. Most people will experience fluctuations in their symptoms as shown in the graph.

On some days you might feel better, on others much worse. Try to remember that in this case, pain is not representative of tissue health or damage, but more a marker of sensitivity, and this can be influenced by all manner of factors - from a poor night of sleep, to a stressful week of work.

Over time, if you are consistent with your exercise and are able to stay positive, you will see an improvement in your symptoms and return to the level you were at before you had the pain!

In Summary…

Here are the main takeaways:

- Pain during exercise is common, especially when starting out. It’s usually not something to be worried about.

- In the vast majority of cases you can find a suitable level to continue your exercise program.

- You can modify resistance training exercises by modifying weight, range of motion or trying a slightly different exercise.

- The rehabilitation process is often up and down but you will improve with time.

References

- Baraki, A., 2021. Pain in training: What do? | Barbell Medicine. [online] Barbell Medicine | With You From Bench to Bedside. Available at: <https://www.barbellmedicine.com/blog/pain-in-training-what-do/> [Accessed 22 October 2021].

- Mosley, G. and Butler, D., 2017. Explain pain supercharged. South Australia: NOI.